Tonight at the Oscars, the record-breaking “Roma” shone bright, winning three Oscars for writer, director, and DP Alfonso Cuaron. Cuaron won for Best Director, Best Foreign Language Film, and Best Cinematography. Its lead actress, Yalitza Aparicio, is already being hailed as a true “star is born,” an indigenous Mexican woman who made her acting debut in this film, and who was up for a Best Actress. Her subtle, muted performance is remarkably elegant, but there are plenty of other similarly quiet yet powerful moments and shots that left me in awe. Warning: multiple spoilers ahead, but you can watch “Roma” anytime, as it’s still streaming on Netflix (and playing in select theaters around the country).

1. The planes at the beginning, midpoint, and end of the movie.

What the planes mean is debatable, but it’s certain that his inclusion of them at these points is intentional. Not only does he want us to notice the planes in the shot, he wants us to hear them, too. It was particularly important to Cuaron that he captured the multilayered, modern Mexico City soundscape, with the roar of jets and traffic juxtaposed against the swishing of mop water on clay tile, tropical birds chirping, and tamale men hollering forlornly down the street. One could guess that the planes signify the transition of Mexico from old world to new, as it grapples with holding onto authoritarian structures amidst a shift toward a modern democracy.

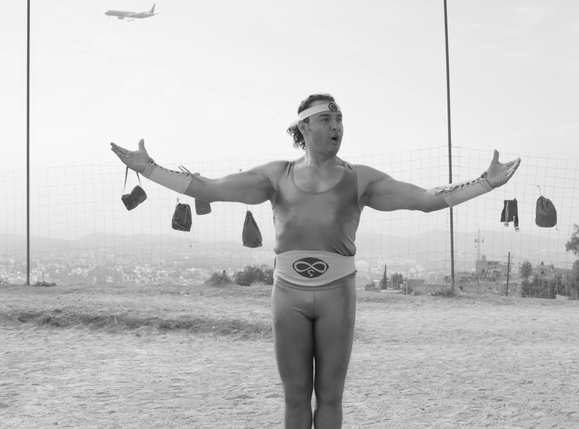

2. A small wildfire, amateur “firefighters,” and a dude in a straw costume singing a death ballad.

This scene was one of the most unsettling in the movie. Fire is often used to foreshadow radical change, so it’s no surprise that they chose to use it here, twenty minutes before an even more gruesome scene of chaos explodes in Mexico City. Looking out over a candle-lined balcony, we and Cleo notice the wildfire in its nascent stage, when it’s only sparks of light illuminating the upper branches of some dried-out trees. Suddenly, everyone on the property has thrown themselves into action; still, while many people scramble to put the fire out–mostly men in sombreros and rebozos, directing the effort– others, notably whiter and dressed fancier, behave like casual observers, still grasping drinks in their hands, pointing at the flames, and treating it as typical vacation sightseeing. Someone even starts setting off fireworks near the fire as it’s happening. Ignorance is bliss.

3. Ragtag bands parading through the streets at opportune times.

If you’ve ever been to New Orleans, you’re no doubt familiar with the sight and sound of a small band of horn players parading down the street just because, and it’s another motif this movie employs.

We see Senorita Sofia (Marina de Tavira, also nominated for an Oscar) process that her husband is leaving her, just as a group of young soldiers passes by and seems to blow right through her. Wracked with helplessness and forced to listen to the invasive, abrasive sound of badly played horns, she becomes a sympathetic character. But there’s something equally ominous about the presence of these amateur military men on an otherwise peaceful street that also subtly hints at a future moment in the film, when the characters find themselves in the midst of government-sanctioned violence.

4. The dog poop in the driveway… yeah, that means something too.

If you’ve ever wondered why Mexican or Latino people tend to let their dogs poop on the sidewalk, well… let’s just say it’s a cultural thing. Most urban city dwellers with dogs in Mexico City didn’t walk their dogs or take them to parks, plastic doggie bags in hand, like we Americans (well, most of us) do today. The family dog, Borros, is a well-loved mutt who uses the driveway as his toilet, and one of Cleo’s many jobs is to wash the driveway of his discardings. When Sofia snaps at her that it’s in need of a cleaning, it’s one of the moments we see how the two women live in markedly different worlds: one of authority and dominance, another of subordination and invisibility. The dog poop constantly reminds Cleo, and us, of their places in the societal hierarchy.

5. Multiple shots of the house with fully packed bookshelves — of course, by the end, which are just stacks.

The family house is an elegant, spacious, well-decorated upper-middle class home, full of books lining antique shelves. When the father moves out at the end of the movie, taking the bookcases with him, what’s left are simply stacks for the family to return home to, adding to a sense of upheaval mirroring that of their lives, not to mention the nation of Mexico. It’s expert poetry and storytelling, sans any words.

6. Cleo saving the kids at the end from the ocean – cleansing, but also demonstrates her completely selfless character.

Cleo is expected to clean, cook, supervise and bond with the children, do laundry, and pick up after the dog… and, if need be, to save the children’s lives. We see her put her own life at risk in a dramatic scene near the very end of the film. I’ve been to Mexico’s coastline before, and know well the strong riptide and relentless waves that can overpower even strong swimmers. Generally, the immersive power of water serves a cleansing purpose in literature and stories. Here, when Cleo emerges, she admits something cathartic: that she didn’t want the baby that was stillborn. The underlying truth, though, is that Cleo is still a hero, as she’s surrounded by the shivering bodies of the children she just pulled to safety, and their grateful mother.

7. $120 and 120 lives lost during the Corpus Christi massacre, upon which the protest scene was based.

When the camera lingers anywhere in any movie, it’s a sign of significance, a way for the director to say, “Don’t look away: this matters.” Cuaron is especially dependent on this technique to instill profound depth and meaning to his cinematography. In the furniture store, mere minutes before gunshots break out and a crowd of young people are attacked by paramilitary thugs, we see a furniture item priced at $120.00. I doubt it’s coincidence that 120 people were killed in the Corpus Christi massacre of 1971.

For black-and-white film buffs, Mexican cultural historians, cinematography geeks, and literature nerds, this film is a treat from beginning to end, utilizing the art of story and the power of visuals hand in hand.

Now I am going to HAVE to see it! Thanks Emily.

I hope you enjoy it as much as I did, Paige! Thanks for your comment. 🙂